This was a message delivered on May 19, 2019, at Dayspring Church in Germantown, Maryland. You can also listen to the audio version (audio version starts a little after the beginning of the message – the first paragraph below is missing). NOTE: Dayspring Church does not have a pastor but uses a shared leadership model in which anyone can sign up to be liturgist, offer a youth message, or preach on any given Sunday. -Bill Samuel

I signed up to speak on this Sunday because it comes closest to the 65th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, not out of a review of lectionary readings for coming Sundays to see which one stirred something in me. However, when I looked at today’s lectionary readings, I found themes which resonate with what I felt led to share. A bit of holy synchronicity, I think.

The Acts reading is all about the question of whether the fellowship of followers of Jesus was just to be Jews or was to include Gentiles as well. The Jew-Gentile distinction for them I believe has some parallels to the white-black distinction in our American context. And what came to Peter from the Lord was graphic and quite clear. Acts 11:12 says, “The Spirit told me to go with them and not to make a distinction between them and us.”

The reading from the Book of Revelation is about the coming of a new heaven and a new earth. The message from the throne in the NRSV starts with, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them as their God; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes.” I wonder if there is significance that the compilers of the NRSV chose the plural “peoples” here. I believe this new heaven and earth, given the evidence throughout the Christian Bible, is one in which the old hierarchical distinctions among different peoples have passed away. We will clearly all be God’s beloved people, regardless of the distinctions among groupings humans have made.

Jesus frequently outraged others by whom he chose to associate with. He repeatedly crossed lines of ethnicity, class, and gender in his ministry. When he tells his disciples in our Gospel reading, “I give you a new commandment, that you love one another” the love of which he speaks crosses those human divisions.

My call to speak this week is primarily to share from my own life, and it arose from reflecting on my life in the light of the Brown anniversary and the reality of racism in the USA. This is the story of one white boy growing up in the USA in a family committed to racial equality.

I was born in 1947 in northern New Jersey, the youngest of four children including twin sisters two years older and a sister four years older. My father was a Methodist pastor at the time. The Church Bishop expelled him from the local Conference when I was still a baby due to his unhappiness about my father’s participation in an interracial prayer group. Subsequently, my father pastored a church in North Dakota for a year, and then in South Dakota for a year.

In 1953, my parents felt a call from God to go to the Deep South. Their response was to get an old truck, pack our belongings in it, and head South. They had no jobs lined up but had a contact point – Koinonia Farm in Americus, Georgia, in the southwest part of the state. Koinonia had been founded in 1942 by two couples as an interracial intentional Christian community committed to racial equality, pacifism, and economic sharing. We headed in our family’s truck and car to Koinonia, where we stayed until we had found and moved to a farm outside of Plains, Georgia, where we lived in a primitive house which lacked indoor toilet facilities and other modern amenities.

We settled into our new home. My parents erected a sign that identified our property as “Brotherhood Acres.” We made friendships with local black families. We heard that one local white person said about our sign, “they mean everybody” which was correct, albeit not a common understanding of the term among local whites. This realization resulted in some local whites harassing us, including the Ku Klux Klan threatening to burn us out. On the designated night, Halloween, they rode by and saw that we did not move out due to their threats and just rode on.

We four children went to Plains Elementary School, the white elementary school for the area. I was in first grade. We found it a somewhat dangerous environment, as we were known as “n*****-lovers” and “damn Yankees” which resulted in considerable hostility towards us, including sometimes being beaten up. A few times we walked the four miles to school, as that seemed safer than braving the school bus ride. Nationally, the most significant thing which happened that school year was on May 17, 1954, when a unanimous Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregated schools were “inherently unequal.” I saw that when our family visited a local black school in the Plains area. It had very primitive facilities, and an inadequate number of very old textbooks in extremely poor condition for the students.

The Brown decision was a great shock to the local whites, who mostly believed strongly in segregation of the races. In the period after the decision, our friends at Koinonia Farm faced greatly increased hostility from the local white community, which had never been very friendly to them. The KKK and other local whites tried -unsuccessfully – to force Koinonia Farm out through bullets, a bomb, and a boycott. Koinonia had some very tough years but survived and is still going strong today.

During the year we were in Plains, my parents were largely unemployed. On rare occasions, my father was able to get day labor. He also preached a couple of times at local churches when the regular pastor was away. One of those churches was the first black church at which I ever worshipped. These rare gigs produced very little income. However, facing adversity together for something we believed in brought us closer together as a family. Because of my parents’ inability to earn a living in that environment, we moved out after a year.

During the next nine years, we lived in a few different communities, either on a farm or in a small town, in the rural Midwest. My father and the Church parted ways, and both of my parents became high school teachers. My family visited around at different churches, and settled down with the Religious Society of Friends, also known as Quakers. None of the counties in which we lived had any African American residents, so all the schools were 100% white. Many of the people in those counties had never seen an African American in person.

This was the era of “sundown towns” – towns with a policy of forbidding African Americans and sometimes other minorities from being inside the town limits after sundown, coupled with other racial restrictions. The communities in which we lived in or near were not formal sundown towns with signs at the town limits, but informally some of these restrictions were imposed by residents and sometimes authorities. We found this in the community of Winterset, Iowa, where my parents taught in the local high school for five years. Ironically, one of Winterset’s claims to fame is that the great African American agricultural scientist George Washington Carver lived and worked there for two years. At the time we were there, not much was said about that, but today Winterset has a park named after Carver and publicizes his connection to the town.

One evening when my parents were coming back from a school meeting in town to our home 12 miles outside town, they came across an African American couple with their baby walking along the side of the road. They stopped to talk to them. The man of the couple was in the Air Force and returning to base in Omaha after being on leave. Their car had broken down on the other side of town. They walked into town and inquired whether the bus stopped there. Although Greyhound stopped in town, they were told it didn’t stop there. They were told to go to the next town, which they were told was 5 miles away although in reality it was 25 miles. My parents took them home to spend the night, and then took them to the bus in the morning.

My oldest sister Pat worked for a time as a waitress in a restaurant on the town square in Winterset.One time, a friend from college came to visit with her boyfriend, who was African American. They stopped at the restaurant to eat lunch, and my sister served them. The owner came over and kicked the couple out and fired my sister. At that time, almost all restaurants in the Midwest had signs saying, “We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.” This incident brought home the meaning of that sign. Pat went to work for another restaurant, where the owner welcomed the business of anyone. One day, a bus full of migrant farm workers came through town and stopped at the restaurant for lunch. The owner was happy for the business, but the Sheriff came and ordered them all out of town.

After the nine years in all-white communities, we went to Urbana, Illinois where my father studied at the University of Illinois. We were active in the local Friends Meeting, and at some point during the year began also to attend the Sunday evening service at an AME Zion Church pastored by the President of the local NAACP with whom my mother worked in a campaign against “urban renewal,” known among civil rights activists as “Negro removal.” I went to the only high school in town, which did include African Americans. This was my first year in an integrated school.

That year I became active in the civil rights movement, and I was arrested at an open housing protest in Urbana’s twin city of Champaign, said by some to have the most segregated housing in the country – African Americans literally lived across the tracks. I was 16, and under Illinois law being arrested meant I had to be investigated to determine if I was a juvenile delinquent. The case worker assigned to my case cleared me on the grounds that someone who participated in a civil rights demonstration was obviously not a juvenile delinquent. At a service at the AME Zion Church, the pastor singled out me and his own 16-year-old son who had also been arrested at the protest as having been baptized by fire.

This was the 1963-64 school year, so segregation in public facilities was still common. African Americans had trouble finding hotels or motels that would accept them when traveling, so they resorted to informal networks. Some friends of my parents asked them whether an African American family whom they knew could stay with us while traveling through. Of course, we said yes. They had a boy about my age and asked if I could take him to get a haircut. We walked to the nearest barber shop, but they said they didn’t know how to cut his hair. The next barber shop said the same thing. The third barber shop we found did agree to cut his hair, although the barber did a poor job. This was in a liberal university town.

The next year my father got a job teaching at a black college, now defunct, in Lawrenceville, Virginia, in the southern tier of the state. Virginia responded to the Brown decision with an official campaign of massive resistance. While the courts rather quickly overturned these laws, it took a long time for many Virginia schools to begin desegregation. For this school district, 10 years after the Brown decision, it was the first year of token desegregation – the “freedom of choice” system in which students could be registered in the school of their choice. Most African American families were afraid to register their children in formerly all-white schools because of the likelihood of losing their jobs. However, a dozen registered for the formerly white high school where I registered, and a few more registered for lower grades in formerly all-white schools. An all-white private academy was formed for white families. Such academies were generally known as segregation academies, or “seg academies” for short. However, a lot of white students stayed in the public schools.

The school district didn’t decide until the last day how to handle transportation. They informed students of their bus assignments by phone. Because the local phone company office refused us service on the grounds we were “n*****-lovers,” they could not notify us. We lived on campus, so I went with a neighbor boy who was one of the school’s first African American students. The district decided on segregated buses, so the driver was surprised to see me but let me on. Our bus ran its main run for the black high school first, so we always got to school late. We also left early, so the bus would be available when the black school let out.

When we got to school the first day, they were having an opening assembly. They read a list of names of students to go to a separate assembly. I was the only one on my bus who was not sent there. In the main assembly they stated, “Normally it is our policy to welcome new students. This year, it is our policy to ostracize new students.” They didn’t use racial terminology, but I think everyone got their drift. At lunch time, I sat down with others from my bus, and that I think is when the school decided to classify me as a “Negro” student.

There was only one white student in the school who would talk to me other than to insult me. One time my science class was in the lab, and the girl who was President of Youth for Goldwater said in a loud voice to someone, “If there’s anything I hate worse than a n*****, it’s a n*****-lover.” I was scared because the teacher was not in the room, but I was not physically attacked.

In that year, I learned to gauge my safety by the color of those around me. When walking down the street in town, I viewed each white person as a potential threat, and each black person as a friend. Because it was such a small community, I expected that most people would know who I was. This was just a tiny taste of what African Americans have experienced year after year, and it followed them wherever they went while I fully benefited from white privilege whenever I was outside of the community.

The county was about 60% black at the time, and blacks had used their economic power to get most white-owned businesses to serve them without overt distinction based on race. However, some white-owned businesses would not serve whites connected with the college, so we sometimes had to go to a business outside the county when we needed something for which there was no local black-owned provider. One Sunday after church, my parents decided they would like to buy a Sunday newspaper. Most businesses were closed on Sunday, but the white-owned drug store was open. My father already knew from his service on the NAACP committee which negotiated with white businesses that the owners of the drug store were among the most hard-core racists in town. When Dad walked in, those working in the store went into the back and would not come out until my Dad left.

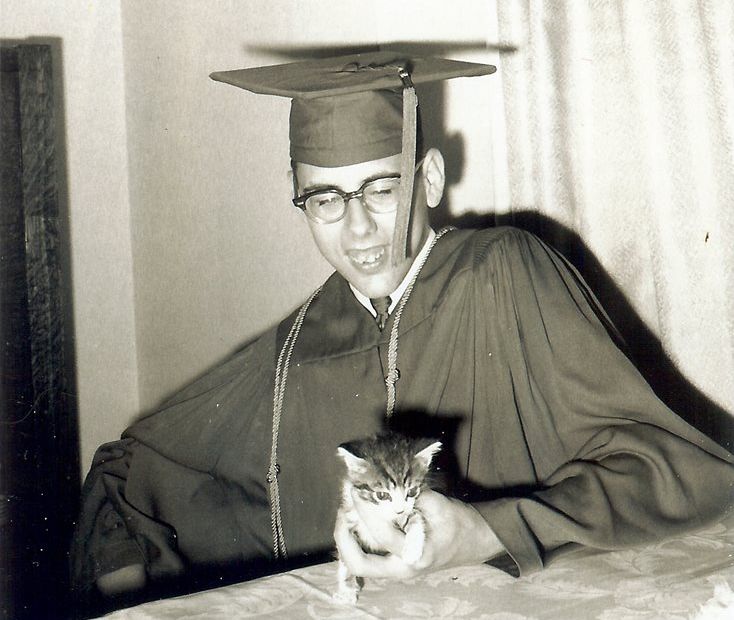

After graduating from that high school, I went to Wilmington College, a Quaker college in Wilmington, Ohio. I thought I was going to the North but found out that Southwest Ohio had some attributes of the South. A black friend of mine at college who was from a nearby town had missed a year of school because the black school had burned down. Wilmington was integrated from its opening in 1871, and when I was there had one of the highest percentages of African American students among majority white colleges and universities in the country. In the 1920’s, the KKK opened an office near the college, and harassed it for some years. This was part of the Wilmington story I learned as a student.

When I came, I was scared that I would be housed in a dorm with a white roommate, which I thought might be dangerous. I was indeed assigned a white roommate, but I liked him very much and we quickly became friends. I began to un-learn my habit of viewing any other white person as a potential threat.

On May 10, scholars from four universities issued a report titled “Harming our Common Future: America’s Segregated Schools 65 Years after Brown“. It found that “intense levels of segregation…are on the rise once again.” Maryland is one of four states in which the majority of African American students attend what the report classifies as intensely segregated schools, schools at least 90% non-white. A major factor is housing segregation. Today we don’t have the legally enforced school segregation by race much of the country had before Brown, but neither do most students attend very diverse schools and, in many areas, different ethnic groups largely attend different schools.

I decided to find out a little bit of what happened where I graduated from high school. In my most optimistic dreams, I imagined the county public schools fully integrated, and the seg academy having closed. In my most pessimistic dreams, I imagined a totally – or almost totally – resegregated situation in which blacks all were in the public schools and whites were all or mostly in the seg academy. The truth turned out to be somewhere in-between. The county is now 55% black, but the public schools are about 80% black. There is only one public high school and one public middle school in the county. The seg academy is still there, but only about a third of the county’s white students attend it. A large majority of white families send their children to what are now predominantly black schools.

Dayspring is in the 3rd most diverse city in the U.S., next door to the 2nd, Gaithersburg. Montgomery County has 4 of the Top 10 most diverse cities in the country. Our County has the most diverse school system in the state and the 103rd most diverse in the country. Yet diversity in our schools varies widely, and several Montgomery County schools are considered segregated by the definitions in the report on the situation at the 65th anniversary of Brown. Both the closest public middle school and the closest public elementary school to Dayspring would be considered by the report as intensely segregated, as they are both 94% minority.

White supremacy is deeply embedded in our culture in the USA. It will take sustained effort over time involving people from all ethnic groups to uproot it.

What are some of the things we need to do as individuals and a community to bring about the Beloved Community in which we recognize our essential unity with all others?

We need to live conscious faithful lives in which we practice what we preach. We need to listen carefully to God’s call on our lives as individuals and as a community, and be obedient no matter what seems to be the cost. We need to measure our “success” more by the degree to which we have been faithful than by concrete outcomes we can readily measure. We need to trust God to use our faithfulness in combination with the faithfulness of others for good. We need to not get discouraged by the evil in the world but press forward to bring about the reign of God.

When my parents decided to uproot our family and head into an uncertain situation without knowing how we would get the resources to support us, they did not have a list of achievements to mark success. They simply went on faith. They disregarded those who warned them against such a venture and said they would be not doing their duty to us as children by engaging in this possibly dangerous journey of faith, instead of making sure we were in quality schools and had material well-being. The education we received by seeing our parents live out their faith was something the finest schools could not have given us.